Tagged: Science

Science isn’t Science without Scientists

In the 10 October 2014 issue of Science, the editors ran a policy article titled “Amplify scientific discovery with artificial intelligence.” The abstract reads:

Technological innovations are penetrating all areas of science, making predominantly human activities a principal bottleneck in scientific progress while also making scientific advancement more subject to error and harder to reproduce. This is an area where a new generation of artificial intelligence (AI) systems can radically transform the practice of scientific discovery. Such systems are showing an increasing ability to automate scientific data analysis and discovery processes, can search systematically and correctly through hypothesis spaces to ensure best results, can autonomously discover complex patterns in data, and can reliably apply small-scale scientific processes consistently and transparently so that they can be easily reproduced. We discuss these advances and the steps that could help promote their development and deployment.

By printing such policy papers, the editors are exchanging one scientific goal (the search for truth) with another (economic growth). This is not the advocacy of scientific progress, but rather the advocacy of science as a means to economic growth on behalf of organized industry — at the expense of individual scientists who will be replaced by “the artificially intelligent assistant.” The burden of proof is on the authors and the editors to show why increasing automation in science will not result in job losses over time.

Growth in Practice

There are good reasons to question the merit of growth as a policy objective.

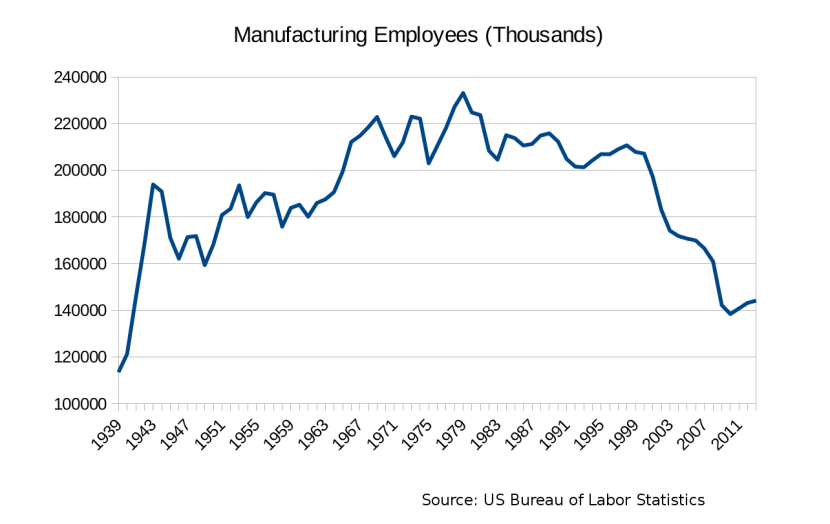

Automation typically means increasing economic growth while decreasing the number of quality employment opportunities: for example, in terms of the raw number of occupations filled, US manufacturing employment is at at levels not seen since just before we entered World War II.

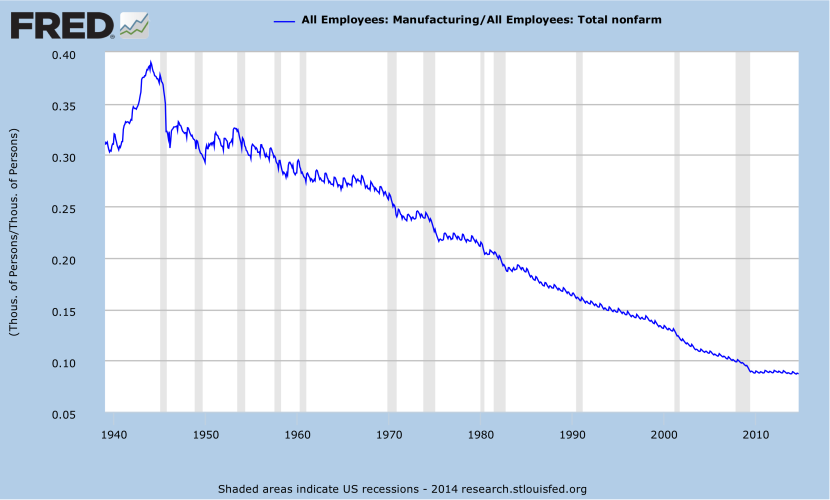

The availability of manufacturing jobs relative to overall job opportunities has also been in steady decline since WWII:

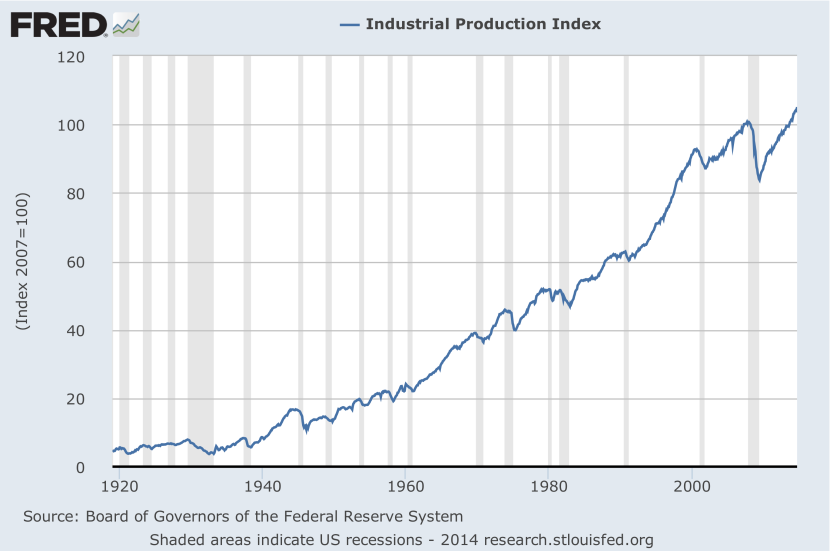

Many of these lost jobs were high-paying union jobs with benefits. Despite these job losses, the value of US manufacturing output has increased over 800% since WWII:

Fewer people yield far more output because of automation.

It is difficult to maintain that increased productivity — though it costs jobs — nevertheless yields a net benefit to society. The value created by increased productivity has not been shared uniformly across the economy: incomes for typical households have been stagnant since 1965. In 1965, median US household income stood at $6,900. Adjusted for inflation this amount equals $50,292 in 2012 dollars. The median household income in 2012 was $51,371, an increase of about 2%. Adjusted for inflation, GDP increased over 360% between 1965 and 2012. Most growth since 1965 has therefore been growth in inequality. Growth means fewer jobs. Increased automation has not meant abundance for everybody, but it has meant a scarcity of high-quality jobs for many.

These macro-economic growth imperatives can lead to additional adverse consequences beyond job loss or wage stagnation. For example, farm prices in the late 1920’s collapsed due to over-production following the introduction of technologies like the tractor and the combine; the problems of industrial agriculture precipitated a broad price control subsidy regime which persists to this day — at taxpayer expense — increasing the cost, complexity and fragility of the food system. As complexity increases, costs increase disproportionately, because increased complexity needs to address the problems created by its own existence. This is a special case of diminishing returns, and can appear in the form of increased managerial overhead.

Increasing automation in science by using AI is likely to have similar unintended consequences.

Internal Inconsistencies

Furthermore, the article published in Science appears to contain a number of internal contradictions which the editors should have caught. If, as the first sentence asserts, “technological innovations are … making scientific advancement more subject to error and harder to reproduce,” then it is hard to see why increasing the role of technologies like artificial intelligence is going to help improve things. If, as the second paragraph states, “cognitive mechanisms involved in scientific discovery are a special case of general human capabilities for problem solving,” then it is hard to see why it follows that the role of humans in “scientific discovery” should be considered a “bottleneck” and therefore diminished.

Specifically, given the large number of scientific null results that are neither written up nor published, it would appear that the authors are making an untenable argument: that artificial intelligence represents an improvement over the unknown efficacy of human research. To make such a case, the authors would need to show that artificial intelligence can learn from a negative or null result as well as a human (which cannot be validated since humans are unwilling to publish such null results). The authors are, in effect, assuming that only positive results are relevant to scientific discovery. By contrast, the Michelson-Morley experiment is perhaps one of the most celebrated negative results of the modern era, paving the way for General Relativity and such technologies as atomic clocks and GPS.

Relevance to the Meaning of Science

In an era where science is no longer a field of human endeavor, but is increasingly automated, Federal science funding can only be an industry subsidy. Any remaining scientists would be become merely means to organized industry’s macro-economic ends. This calls into question the very meaning of science itself as a human endeavor, but offers no solutions.

To ask a similar question: consumers may purchase and enjoy literature written by algorithms, but should they? Is it still properly literature if it doesn’t reflect the human condition? Ought we not educate young people to enjoy the experience of exploring the human condition and our place in the Kosmos? Or has the promise of secular humanism run its course, and the classical University education given way to an expensive variety of technical training, by means of which one takes on debt to procure a new automobile every few years? Is that now the meaning of life? Is this a new age of superstition and barbarism, where technology “advances” according to privileged seers who read the entrails of data crunched by the inscrutable ghost in the machine, waiting for a sign from the superior intelligence to come shining down from the clouds? So much for the love of learning.

These are not simply rhetorical questions, for if automation makes science as we know it obsolete, then there is — if nothing else — a substantive policy debate to be had where the federal science budget is concerned.

Truths Hidden in Plain Sight

In the 18 July 2014 issue of Science, Kendra Smyth reviews the new book “The Sixth Extinction” by Elizabeth Kolbert. The book documents past mass extinction events and situates the present loss of biodiversity — due to human activity — within this context.

If it is the case — as Smyth writes — that “with warp speed humans are responsible for transforming the biosphere” and that “humanity is busy sawing off the limb on which it perches,” then this state of affairs would seem to draw attention to certain un-examined assumptions behind statements like “humans have succeeded extravagantly.”

Specifically: perhaps our characteristic intelligence is not at all a survival advantage, but rather a genetic fluke, and the relative youth of our species (behaviorally-modern humans are roughly 50,000 years old) may then simply indicate that natural selection hasn’t yet gotten around to knocking us off the food chain. Perhaps this is a hypothesis better left untested. Perhaps we’re only “succeeding” insofar as we’re eliminating ourselves faster than natural selection eliminates other species.

It would also seem that the West’s post-Renaissance preoccupation with technological progress conceals an irrational vestige of our religious heritage: an irrational faith in a technological savior to the eschatological trajectory of technology. That is, we eagerly anticipate a technological solution to the problems created by technology. Given that modern technology is only 300 years old (beginning with the Newcomen engine in the early 1700’s) there is very little evidence in the history of the human race to support the view that technology will solve the problems of technology, making such beliefs very much an article of faith.

To quantify the aforementioned state of affairs, it may be worth beginning with an honest discussion of the heresy of diminishing returns. If one looks at the productivity of the US healthcare system, for example, we see a straightforward diminishing returns curve:

The meaning of the above chart is that relatively few medical innovations have made a substantive difference in quality of life and overall health outcomes: sanitation and hygiene (in the mid-1800’s, Ignaz Semmelweis at Vienna General Hospital decided that doctors should wash their hands), anesthetics and analgesics (patients used to die of shock during surgery), antibiotics (developed for around $20,000 of basic science research), and the vaccine. Since then, modern medicine has been largely concerned with addressing the problems of technological civilization, such as poor diet, sedentary lifestyle, and environmental pollution. And medicine has been growing exponentially more expensive. Unfortunately, there are few patents to be found where a change in cultural values is what is needed: you can’t patent a healthy diet and exercise, so well-funded science turns its attention elsewhere.

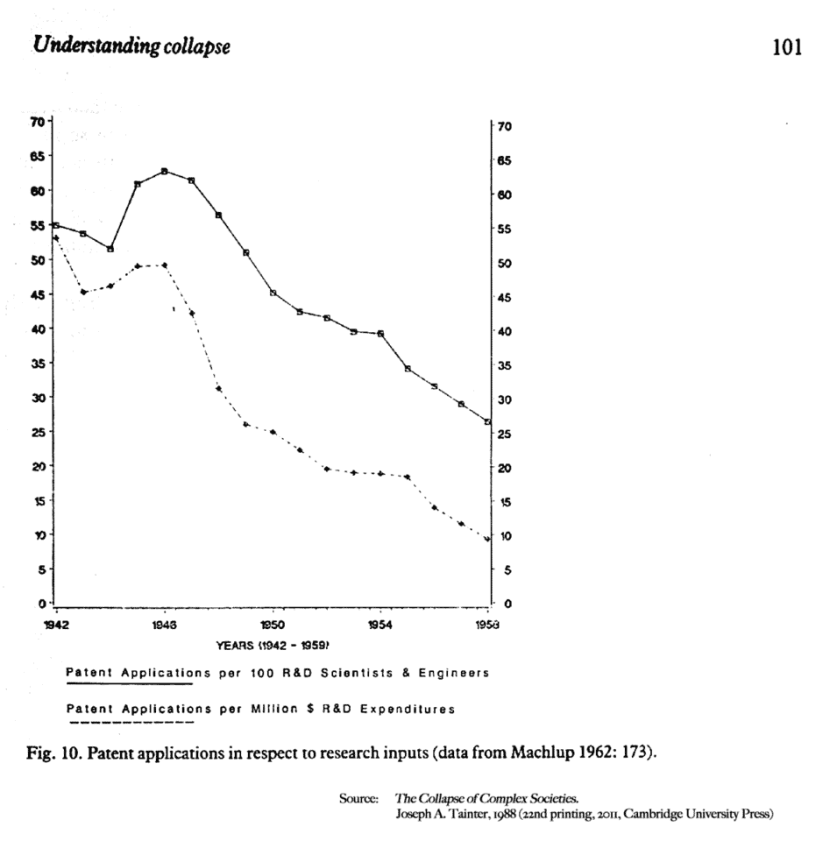

Although diminishing returns is a well-documented economic phenomenon, it receives scant discussion in the mass media, which is otherwise filled with breathless accounts of the latest and greatest gadgets. The phenomenon is by no means limited to the healthcare industry, but appears throughout the economy. If one looks at, for example, the cost per patent over time, a similar curve emerges:

The above chart illustrates a simple point: patents get more expensive over time because most of the easy and most pressing problems get solved first. The diminishing marginal utility kicks in as more specialized patents affect fewer numbers of individuals, in contrast to patents with a more broad applicability that affect many people.

Here is what diminishing returns on investments in technology mean in cultural terms:

Fracking is a new energy extraction technology with many harmful consequences, including heavy water use, irregular seismic activity, and environmental pollution. Fracking is becoming an increasingly popular way of extracting energy for two main reasons: politically, Americans don’t want to depend on foreign energy sources; and, culturally, Americans want to persist in destructive, wasteful habits. Driving in automobiles is inherently wasteful, as over 2/3 of the energy purchased as gasoline is not converted into motion, but rather lost as waste heat. Fracking is a harmful technology designed to preserve a wasteful mode of transit for cultural reasons. Busses (measured in passenger miles per gallon), trains, and urban living are by far more energy efficient and less environmentally costly.

Many Americans delude themselves about their habits by purchasing “green” products like hybrid automobiles. While hybrids produce fewer emissions while in operation, they are more complex than conventional automobiles, use more energy-intensive materials, and they rely on toxic chemicals for their batteries, so that, on the whole, they may actually produce more pollution than typical internal combustion engines. If one purchases a hybrid with the goal of reducing carbon emissions, one would do better to adopt a vegetarian diet. Doing so reduces carbon emissions, reduces antibiotics use, lowers medical costs by improving diet, and reduces animal cruelty, without further concentrating wealth in the hands of the industrial system that profits from marketing “green” products that aren’t actually all that “green.”

Dietary modification, despite its advantages, requires self-control and a change in cultural values. Unfortunately, scientific and technological “progress” plays the role of an enabler for bad habits. These bad habits seem poised to wipe our species off the face of the planet.

Theses on Technological Progress

Assuming technology always “evolves” better versions is medieval thinking. This way of thinking about technology only makes sense if one assumes that Man is on top of Nature’s Great Chain of Being, and that technology, our prosthesis, is made in our image, as a Microcosm of Man.

Technology doesn’t “evolve,” it’s designed. The modern understanding of “design” originates in the European Renaissance.

Technological “evolution” exhibits some features of reproduction with variation, but these variations are determined by design, not by natural selection.

Markets may resemble natural selection in certain cases, but “competition” — which drives evolution under the model of natural selection — is not a defining feature of today’s organized industries.

Commercially-produced industrial technologies are often released in successive iterations, but to consider each iteration as a sign of “progress” makes a categorical error.

Progress is a teleological concept: it is goal-oriented. One makes progress along a line from A to B. “Intelligent design” is also a teleological concept because it involves God having a plan for Man.

The technological iterations commonly deemed “progress” involve complex tradeoffs that are often qualitative in nature.

The modern concept of “progress” originated in the European Enlightenment, which was defined by the cultural rediscovery of Classical wisdom from antiquity.

In action, “progress” does not entail improvement, nor does it implicate “advancement” as the word might be understood in the “pure” sciences.

With respect to technological “progress,” consider a case in point: the mobile phones of today offer inferior voice quality with a more fragile connection than the landlines of yesterday. The wireless capability of mobile phones may offer one advantage over our natural limitations, and the ability to speak at a distance another, but, as cultural artifacts, telephones neither directly nor by analogy “evolved” the ability to send and receive text messages, in response people tiring of habitually speaking into them.

Pollution is by and large a problem with commercial technology. Yet with religious fervor, most people unquestioningly believe there is a technological solution to the problems of technology. This assumption may prove disastrous for anybody reading this, or their children, or their grandchildren, but it will happen that soon.

David Pogue on Memory

The August, 2013 issue of Scientific American features a grossly irresponsible column by David Pogue. The column, titled “The Last Thing You’ll Memorize,” suggests that perhaps mobile internet appliances have made memorization obsolete, arguing by analogy to the electronic calculator’s effect on upper-level math classes. Arguments by analogy are a rather tenuous way to make a point, and Mr. Pogue’s argument is no exception.

Mr. Pogue writes: “As society marches ever forward, we leave obsolete skills in our wake. That’s just part of progress. Why should we mourn the loss of memorization skills any more than we pine for hot type technology, Morse code abilities or a knack for operating elevators?” The sentiment doesn’t appear to be intended as an intellectual provocation. Mr. Pogue even appeals to the wisdom and technological foresight of his child, who — because of “smart phones” — couldn’t imagine “why on earth should he memorize the presidents” from his own country’s history. Students are allowed to use calculators on school exams, Mr. Pogue reasons, so why shouldn’t students be allowed to use “smart phones” to save them the trouble of having to remember things?

To extend Mr. Pogue’s argument slightly: does word processing make spelling obsolete? Do students no longer need to memorize all the idiosyncratic spellings found in the English language? Should we conclude that literacy is an obsolete skill? Should we simply forgo novels in favor of movies, since cinema is a newer technology?

The flaws in Mr. Pogue’s reasoning begin with his choice of metaphor, though the reasoning behind his choice to argue by analogy fails on closer inspection as well. While we may not exactly “pine for hot type technology,” there are a wide range of positive social values attached to the preservation of historical skills. Laser toner hasn’t replaced printing and engraving in all cases: artists still make etchings, photographers are still interested in the craft, quality, physicality, and historical relevance of chemical photography, artisan printing presses still set type, and most global currencies involve an active social role for the older, traditional skills, required for coining currency and printing bills.

New technology doesn’t always replace old technology; this is a biased view of recent history, promulgated to justify commercial planned obsolescence in the face of diminishing returns. Often enough, new technology simply gives old technology a new value. The tourist economy of Williamsburg, Virginia, depends on maintaining skills, architecture, and other cultural practices from the Colonial Era, as a sort of living museum. Artists still practice ancient pottery skills, often producing original artifacts of greater economic value than comparable mass-produced items. Cubic zirconium hasn’t replaced diamonds in engagement rings. Just because “Morse code abilities” are no longer a marketable skill, there are historical documents and records containing Morse code and references to Morse code, and preserving knowledge of these valuable artifacts for future researchers is part of what Universities do. And, while one may have trouble today landing employment with “a knack for operating elevators” — since automation and computerization now take care of these jobs in places like classy hotels, or high-rise office buildings — it may well be worth mourning how many paying jobs automation has replaced and continues to replace, especially given the current state of the labor market, and the bleak prospects for millions upon millions of indebted college graduates. Even the grocery store cashier appears to be an endangered species these days.

So, to consider Mr. Pogue’s central analogy — that of the calculator — we should begin by pointing out that while we may say that a calculator is good at math, we don’t conclude from that fact that it is smart. Branding aside, “smart phones” aren’t smart because they can substitute for human memory in some cases. The reference capabilities of “smart phones” may create opportunities for new skills — such as, an ability to formulate queries that will identify a factual needle in a haystack — this is quite different from saying that such a new skill can occupy and replace the role of memory. The value of a “smart phone” as a source for reference material is also highly contingent upon the quality of the source a user chooses to rely on: absent some sort of peer review process for Google listings, this would seem to be at the very least a precarious substitute for the sort of intellectual cannon with which students are typically acquainted through education. It is worth noting, on this last point, that books didn’t replace memory, even after the printing press made it cheap enough to fill libraries: the recording and storage of facts in books and libraries serve to make knowledge more accessible — not to replace memory — and Mr. Pogue provides no real evidence that Internet search engines are qualitatively different in this regard.

To further address the issue of online source material, Mr Pogue’s argument also assumes that the future of the Internet will look like it does today, with vast quantities of relatively high-quality material available at no cost. This may not be a safe conjecture at all: more and more corporations are looking for more ways to make money by offering proprietary services online. Bloggers may want to start getting paid for what they write. Commercial media outlets are erecting “pay walls,” FaceBook keeps its user-contributed content walled-off from Google and the public Internet, peer-to-peer networks are being challenged by legal action coordinated with competing commercial services backed by large corporations, and electronic surveillance may exert a chilling effect on what independent platforms are willing to publish, or what individuals are willing to read. The laws surrounding intellectual property rights are highly contentious at this point in time, affecting what types of reference material may be shared or quoted from, and in what manner.

Mr. Pogue concludes his argument by analogy by asserting: “Calculators will always be with us. So why not let them do the grunt work and free up more time for students to learn more complex concepts or master more difficult problems? In the same way, maybe we’ll soon conclude that memorizing facts is no longer part of the modern student’s task. Maybe we should let the smartphone call up those facts as necessary…” Beyond the aforementioned problems with Mr. Pogue’s assumptions about the character and quality of the information that will be available on “smart phones” in the future, there is an internal contradiction here in his position: if “progress” tends to continually replace technologies that once seemed current, on what grounds does Mr. Pogue suppose that the capabilities of today’s “smart phones” will remain stable enough to re-organize educational curricula around them? Every five-function calculator performs subtraction and multiplication in an identical fashion, but Google is not “objective” in the same way, and customizes search results based on a user’s past search history. What if one “smart phone” manufacturer blocks out Google access due to the terms of some other licensing agreement? Will it really “free up more time” if students need to use trial-and-error techniques to formulate queries on search engines, rather than simply recall the fact they’re looking for? If “memorizing facts is no longer part of the modern student’s task,” by what standard then will students be able to recognize whether a piece of information they retrieve from a search engine is reliable or not, or whether an argument they come across is historically well-grounded? Students could simply defer to the authority of certain trusted sources, but doing so would undermine Mr. Pogue’s advocacy that students “focus on developing analytical skills.”

But to look past the analogy, and to get to the point: many people consider loss of memory function one of the most terrifying prospects imaginable. Amnesia may be a staple in soap operas, but Alzheimer’s disease is a reality for many Americans. Loss of memory function is clearly a mental handicap. Any chess player will tell you that the ability to remember the past few moves is at least as important as the ability to project a few moves into the future: if you don’t keep track of what your opponent is doing, you can’t identify your opponent’s strategy. If you can’t remember a series of articulated statements, you can’t follow an argument. Memory is the basis of learning, and therefore of knowledge, and, by extension, wisdom. Deprecating memory skills is a recipe for a population of morons and zombies. If we don’t teach students how to remember things, we not only deny them the promise of education itself, but we deny them the basic skills needed to think strategically.

Is Michael Shermer Really a Skeptic?

In the June, 2013 volume of Scientific American, Michael Shermer’s reply to a reader’s published letter makes a number of remarkable statements. Shermer was attempting to clarify or otherwise augment the meaning of his February, 2013 column, “The Left’s War on Science.” In discussing how “the ‘anti’ bias can creep in from the far left,” Mr. Shermer suggests that “Perhaps instead of ‘anti-science’ it is ‘anti-progress’” that is the real issue with the political left. I would like to address the implicit normative biases inherent in Mr. Shermer’s equating of “anti-science” with “anti-progress,” to which he seems to give ascent un-skeptically. Granted, he is not identifying the one with the other, but he does equate them, and this reveals a bias.

First, there is the more superficial bias contained in Mr. Shermer’s choice of phraseology, specifically, the use of an oppositional definition employing the prefix “anti” to specify his referent, the sense of which implies a normative value judgement given the popular discourse around such diverse spheres as “technology” or “freedom.” Who in their right mind is against “progress?” If automation is replacing our workforce, maybe “anti-progress” is also “pro-labor.” If cheap integrated circuits are the product of dubiously sourced coltan, maybe “anti-progress” is “pro-human rights.” If more automobiles make more pollution (because increased fuel economy doesn’t fully offset the increasing carbon costs of extracting energy from less accessible reserves), and if more fuel-efficient automobiles furthermore compound other state-centric financial problems (such as the market consequences of ethanol mandates on subsidized industrial agriculture in the US, or on third-world grain prices for what are otherwise staple food crops on the global market), maybe “anti-progress” is “pro-ecology.”

Or, to phrase the same difficulty in slightly different terms: do we really need more “progress” in the breeding of more productive grains, or is it maybe better to use culture to encourage a more comprehensive ecological view of the individual in the world, and to simply stop throwing out half the food we produce each year, or only eat meat three times a week instead of three times a day? Is it possible that these “ecological” solutions are not only less complex than new networks of industrial processes, but can also be more resilient and cheaper and more pleasurable to partake in? Would it be anti-progress, for example, to advocate for reducing unemployment by increasing labor-intensive organic food production for a less meat-centric diet, that is also less wasteful, more full of substantive choices and alternatives, and healthier?

Second, there is the bias conveyed by Progress itself, which Progress invokes in favor of itself, and for its own perpetuation, wherever Progress is invoked. Progress is a relatively new ideology in Western culture, dating for our purposes to the European Enlightenment. It says, basically, that things always improve through the mass accumulation of specialized, systematic knowledge and the mass dissemination of its applications. In a commercial sense, it means newer technology is always better and must also replace older technology. This ideology is relatively new. The European Renaissance, by contrast, venerated the wisdom of Antiquity; in Medieval Christendom things were better back in Eden; and in Rome, the mythic Golden Age of the remote past offered the ideal model for future aspirations. Even Francis Bacon, famous advocate of the “advancement of learning,” conjured up the long-lost Atlantis in his utopian manifesto on the future of the mathematical arts.

Looking more closely at such normative terms in their popular usage (to wit, “anti-progress”), certain flaws in the ideology’s positive formulation become apparent. A case study in terminology: if we look at bees, we can see they are a much older species than modern homo sapiens. They outnumber us, have been more successful at propagating their genes than us, and, in a sense are therefore “more evolved” than us. Are bees “better” than humans because they are “more evolved” or otherwise “more successful?” Consider this: if “progress” drives our species to destroy our own habitat, maybe our big brains aren’t really all that great of a survival advantage after all — or maybe, at least, it’s a little lunatic to talk about human intelligence in such superlative terms, as if our absolute superiority were a settled matter. I think the jury is very much still out on this: the average mammal lasts about a million years, so it’s really not like modern humans are a model of Malthusian-Darwinian longevity. Maybe Neanderthals really were better, and we out-competed them because we’re a genetic fluke, a virus, that will eventually consume itself by consuming its host — and though we would declare ourselves victors over Neanderthals, perhaps the cosmic hammer of natural selection just hasn’t landed quite yet, for our stupidity in destroying our living past. Which is not to suggest I am arguing against rationality or engineering, or Enlightenment values: to start building a metaphor from our case study in terminology: bees conduct their affairs with a lot of remarkable, organized, rule-governed social behaviors — and they do so with very little brain. With just a little more than what a basal ganglia can do, they might make a suitable metaphor for those same Enlightenment social values that produced that grand edifice of civil law our nation so highly esteems.

Third, there is the teleological component to Mr. Shermer’s particular choice of the term “progress” that can easily lead to false inferences about the ideology and its historical consequences. Specifically, “progress” implies progress towards something: you progress from A to B. “Progress” broadly understood, however, is more properly analogous to the way a scientist might talk about a body part being “designed” to accomplish a particular purpose, or an electron “liking” to do different things under different circumstances. Scientists in such cases aren’t really making teleological claims, though they are making a case for a structured set of circumstances. Perhaps, in empirical terms, human civilization is making progress towards catastrophe — be in environmental ruin or thermonuclear war.

What qualifies as “progress” in one context may be more usefully described as a type of normative bias, when the term’s usage is considered more broadly. Although it is easy to see that computers have replaced typewriters and wireless phones have replaced landlines in many cases, and we all agree these developments are more convenient in certain ways (though they also facilitate undesirable behaviors, such eavesdropping or distracted driving), these media-centric cultural touchstones are really of limited historical validity where “progress” is concerned. Computers have not replaced paper, or pens, or books, or the written word, or the value of “movable” or otherwise dynamic type: older technologies aren’t always replaced, though their role changes.

Many electric guitarists today seek out amplifiers driven by vacuum tubes, which are still sold for this purpose, and some musicians prefer to record onto analog tape, or to release new recordings on vinyl. This is normal. As of the year 6013 A.L., some 30% of computers are running Windows XP, a 10-year-old operating system. Outdated technology is the norm: there are six times as many users of the outdated Windows XP as there are Mac users, Apple’s stock price notwithstanding. Which is to say, equating (or, perhaps more properly, conflating) “technology” with “the newest technology” under the rubric of “progress” reflects a bias.

Lastly, there is the wisdom of the ages, which Progress would amputate from our intellectual heritage: Futurist architect and Italian Fascist Tomasso Marinetti apparently wrote persuasively in 1914 about this devastation of living history, embodied in historical buildings and common urban forms, how it represents “a victory for which we fight without pause against the cowardly worship of the past.” His vision was realized in many mid-sized American cities in the 1960’s and 1970’s, when historic downtown areas across the country were razed to make way for Interstates and parking lots and parking garages for suburban commuters. This same razing provided the match to ignite many of the the urban riots during the late 1960’s, and initiated a decades-long program of planned neglect in inner cities nationwide, while suburbs parasitized both cities and rural areas in the guise of an aggressive modernity.

Proverbs 6:6-8 reads: “Go to the ant, thou sluggard; consider her ways and be wise: which, having no guide, overseer, or ruler, Provideth her meat in the summer, and gathereth her food in the harvest.” The organization of ant society is profoundly decentralized, but also profoundly social and cooperative. The US Constitution is similar: it speaks of the “common defense,” the “general welfare” and “our posterity” but also of “the blessings of liberty” and of “Justice.” The ant is properly feminized in King James to accord with the Greek Sophia — Wisdom — in the same manner as other Biblical sayings, such as Proverbs 8:1 (“Doth not wisdom cry? and understanding put forth her voice?”) or Matthew 11:19 (“The Son of man came eating and drinking, and they say, Behold a man gluttonous, and a winebibber, a friend of publicans and sinners. But wisdom is justified of her children”). The teachings of Freemasonry take this basic appeal and apply it to secular society, in a Neoplatonist fashion, modeled after Plato’s utopian discourse on the ideal State.

Freemason Albert Pike — the only Confederate officer to be honored with an outdoor statue in DC — fashioned a highly inter-textual dialog called The Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry. A compendium of Renaissance wisdom synthesized with the tools of Enlightenment systematic inquiry, the text represents a sort of Machiavelli of morals. Chapter VIII reads in part: “A Masonic Lodge should resemble a bee-hive, in which all the members work together with ardor for the common good… To comfort misfortunes, to popularize knowledge, to teach whatever is true and pure in religion and philosophy, to accustom men to respect order and the proprieties of life, to point out the way to genuine happiness, to prepare for that fortunate period, when all the factions of the Human Family, united by the bonds of Toleration and Fraternity, shall be but one household,–these are labours that may well excite zeal and even enthusiasm.”

Which is to pick up the Solomonic wisdom from the Proverbs, by adopting an animal that is industrious and well-organized like the ant, though less inclined to warfare, and also an ardent lover of beauty. Plato had Socrates say it similarly, in urging us to craft the works of a “fine and graceful” social order “so that our young people will live in a healthy place and be benefited on all sides, and so that something of those fine works will strike their eyes and ears like a breeze that brings health from a good place, leading them unwittingly, from childhood on, to resemblance, friendship, and harmony with the beauty of reason.”

So I went and revisited Mr. Shermer’s February 2013 column, as I had that month’s magazine still on the table in my study. The column’s hook promises to explore “How politics distorts science on both ends of the spectrum.” I would rather have read someone argue from that starting point something more to the effect that “both ends of the spectrum” accept ideological “progress” so unquestioningly, that alternatives with their repercussions are almost inconceivable, and that this is a far greater problem, because it induces systemic blindness that is threatening the civilization whose values Mr. Shermer purports to defend.